Let’s begin at paragraph 1.67, which explains what a colophon is. If you flip to the last page of a book, such as, to pick a completely random example, The Chicago Manual of Style, you might find some information about the book’s production.1 Great job, you found a colophon! CMOS’s colophon tells us about who and what were involved in the design, typesetting, printing, composing, and binding of the book.

Etymology side note! The word colophon comes from Latin and Greek and earlier languages, and it means hill! You know, like the one I was ready to die on! So that’s a fun connection there.

I also poked around in the Wikipedia entry on colophons, which quickly led me into the delightful world of book curses. Long story short: prior to the invention of the printing press, preserving the written word was super labor intensive, and it was a huge bummer if someone stole your clay tablet or scroll or manuscript. Naturally, the state-of-the-art anti-theft technology was a curse. By medieval Europe times, the curse was often found on the last page of the book, hence the connection with colophons.

There’s an entire book just about book curses. It’s called Anathema! It’s free on Internet Archive! It’s a fun way to spend an afternoon! A lot of the time, the curses promised shunning and excommunication, but bodily-harm-based curses were also popular, like: “May he who steals it suffer from violent bodily pains.” (p. 75)2

Sometimes they got more colorful, like this one: “If anyone take away this book, let him die the death; let him be fried in a pan; let the falling sickness and fever seize him; let him be broken on the wheel, and hanged.” (p. 88)

I applaud the creativity here, but I also have questions about the order of operations. Letting him die the death is the first in a list, though I can’t imagine the author intended that to be the first step. Being fried in a pan and having fever wouldn’t be much of a bother if you already died the death. So let’s assume the rest of the phrases are specifying the manner of death dying. (Or maybe what’s translated as “die the death” had some other meaning in Latin at the time! If you’re a medieval Latin expert, nothing would delight me more than to hear from you!) Even so, after you’ve already been thoroughly sautéed, I’m not sure fever is going to be that much of a hassle for you.

Or this one:

Who folds a leafe downe

ye divel toaste browne,

Who makes marke or blotte

ye divel roaste hot,

Who stealeth thisse boke

ye divel shall cooke.

(p. 110)

Here we have punishments for dog-earing, writing in the book, and stealing it. I would expect a relatively minor curse for dog-earing, but this scribe gets right in there wishing the devil to toast the offending dog-earer brown. I feel like stealing is way worse than dog-earing, but the punishment for theft is being cooked. Once you’ve been toasted brown, how much of you is there left to cook? I guess this is a real “in for a penny, in for a pound” situation.

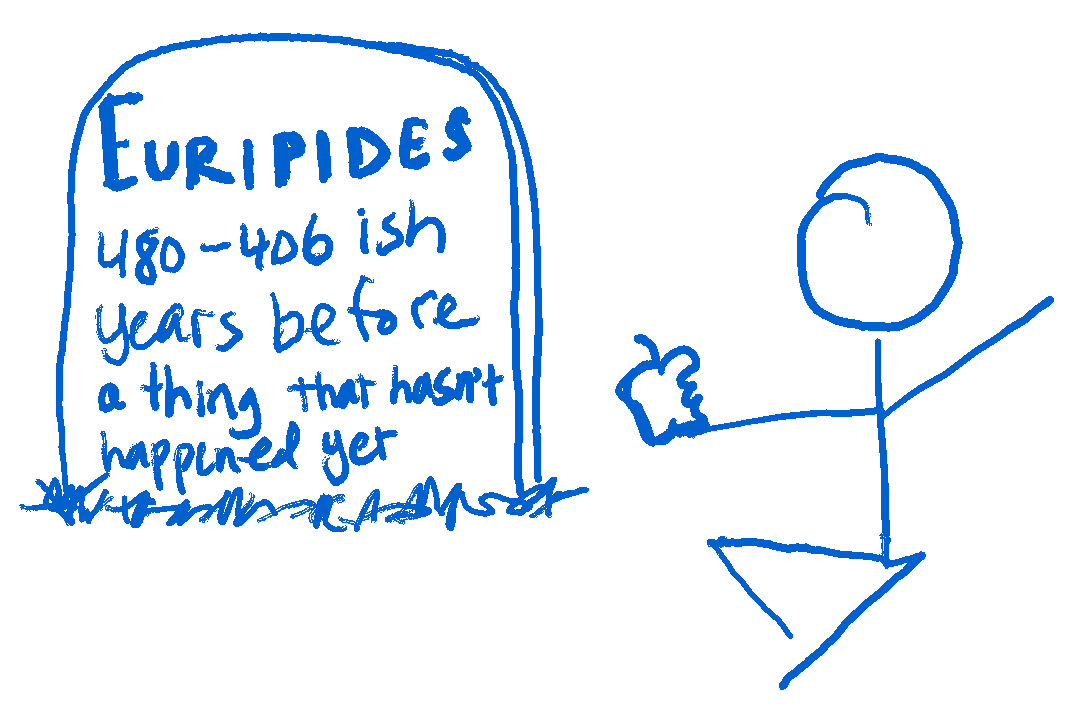

And I’ll leave you with this one: “If you rub me out, I will slander you to Euripides.” (p. 57) This was written several hundred years after Euripides died, so I suppose it wasn’t meant literally, but I do like to imagine this scribe taking a sack lunch out to Euripides’s grave site, plopping down, and making up a bunch of lies about everyone who smudged up his book. (This led to me googling “where was euripides buried”, which I feel good about.)

Paragraph 1.69 notes that the word “colophon” can also be used to refer to a publisher’s logo. That seems needlessly confusing to me!

I don’t know, man, if you want an effective deterrent, you might have to threaten with more than the equivalent of “I ate too much cheese and ice cream today”. (Or perhaps that’s just me.)